17th October, 2020

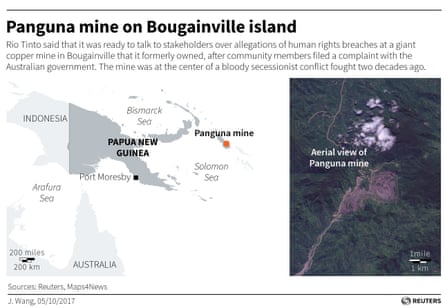

[By Leanne Jorari and Ben Doherty] Panguna mine is often cast as the economic key to Bougainville’s potential independence, but young MP Theonila Matbob says her people, and their land, must come first For all of Theonila Roka Matbob’s three decades, the scar on her land that was once the world’s largest copper mine has cast a pall. The Panguna mine in Bougainville, eastern Papua New Guinea, has not yielded a single ounce in her lifetime – forced shut the year before Matbob was born – but she grew up in the shadow of the violent civil war it provoked.

When she was just three years old, her father, John Roka, was murdered by the secessionist soldiers who had forced the mine to close. Spending years in a “care centre” run by the PNG defence force, she remembers a childhood dominated by an all-pervasive fear, where the sound of gunshots regularly rang out across the valley, where neighbours disappeared from their homes, their bodies later found slaughtered.

Theonila Roka Matbob stands in front of the Pangua mine in Konawiru, Bougainville. Photograph: Human Rights Law Centre/Reuters

There is peace now, but memories remain, and “we live with the impacts of Panguna every day,” Matbob says.

“Our rivers are poisoned with copper, our homes get filled with dust from the tailings mounds, our kids get sick from the pollution.

“Every time it rains more waste washes into the rivers, causing flooding for villages further downstream. Some communities now have to spend two hours a day walking just to get clean drinking water because their nearby creeks are clogged up with mine waste.”

Families live in the disused mine pit at Panguna, attempting to make a living from alluvial mining. Polluted, unnaturally blue water, contaminates the pit and there are frequent landslides. Photograph: Supplied/Human Rights Law Centre

Panguna is quiet these days. The mining trucks lie rusting in Bougainville’s clammy heat; the massive pit carved into the middle of a mountain is inhabited by a handful alluvial miners, digging with hand tools for what gold remains; and the Kawerong-Jaba river delta downstream is flooded with bright blue toxic waters which poison the land and the people who live there.

Bougainville independence high on agenda as Ishmael Toroama elected president

And Matbob, the little girl who grew up in the shadow of the mine’s violence, is now a parliamentarian, determined to seek redress for her people. Newly elected to the Bougainville parliament for the electorate of Ioro, which encompasses Panguna, Matbob has led a formal complaint filed with the Australian government against Rio Tinto for environmental and human rights violations caused by the mine.

The complaint, supported by more than 150 members of her electorate and by the Human Rights Law Centre, alleges that the massive volume of waste pollution left behind by the mine is putting communities’ lives and livelihoods at risk, poisoning their water, damaging their health, flooding their lands and sacred sites, and leaving them “in a deteriorating, increasingly dangerous situation”.

A toxic legacy

Panguna was an immensely profitable mine. Over 17 years it made more than $US2bn for the mine’s former owner and operator Rio Tinto, who pulled 550,000 tonnes of copper concentrate and 450,000 ounces of gold from the mine in its last year alone.

At one point, Panguna accounted for 45% of all of PNG’s exports, and 12% of its GDP.

But for those whose land it was, Panguna brought but a sliver of the wealth and development that was promised – less than 1% of profits – leaving behind a legacy only of division, violence, and environmental degradation.

In 1989, amid rising fury at the environmental damage and the inequitable division of the mine’s profits, customary landowners forced the mine closed, blowing up Panguna’s power lines and sabotaging operations.

A mining truck rusts at Panguna mine. Photograph: Ilya Gridneff/AAP

The PNG government sent in troops against its own citizens to restart the foreign-owned mine – at the behest of Rio, it says – sparking a civil war that would rage for a decade. Along with a protracted military blockade, it led to the deaths of as many as 20,000 people.

Rio Tinto cut and run, and has never returned to the island, claiming it is unsafe, despite pleas from landowners to repair the vast and ongoing environmental damage.

“These are not problems we can fix with our bare hands,” Matbob says. “We urgently need Rio Tinto to do what’s right and deal with the disaster they have left behind.”

‘We expect a fair share’

A product of Bougainville’s matrilineal society, which bestows women with custodianship of land and community authority, Matbob speaks quietly but forcefully.

A teacher by profession, and mother of two, she studied at universities in Madang and Goroka before working as a social worker and running for parliament. She beat a field of 15 candidates, including several former revolutionary soldiers, and even her own brother.

But the parliament to which Matbob has been elected has another primary and overwhelming concern, though one intimately related: negotiating independence from Papua New Guinea.

Last year, the province voted 98% in favour of seceding from Port Moresby, and the new president, former Bougainville Revolutionary Army commander Ishmael Toroama, has promised to deliver liberation.

Despite resistance from PNG’s government to losing its resource-rich eastern province, there is genuine expectation amongst Bougainvilleans that their decision to secede will be honoured.

Upe men line up to vote in the 2019 independence referendum in Teau, Bougainville. Photograph: Jeremy Miller/AP

But the argument allied to political independence in Bougainville is that it can only be achieved alongside economic autonomy.

To that end, the argument runs, re-opening Panguna is the surest, perhaps the only, way a small province of just 300,000 people can survive as an independent nation. On Bougainville, the issue of independence has become inextricably linked to that of resources, for which Panguna has become a grim synecdoche.

“Large-scale mining provides a route to fiscal self-reliance, but this strategy has risks,” a report by Dr Satish Chand for the National Research Institute of PNG found, arguing of Panguna, “the viability of this project, the… profitability of the mine, and the revenues generated for… government are all speculative”.

Deeply embedded in Bougainville’s political psyche is a belief in the transformative power of political and economic independence – most likely achieved through mining – to bring prosperity, development and stability after decades of turmoil and privation.

But those expectations may prove difficult to marry with reality: an independent Bougainville would likely face a revenue shortfall of tens of millions of dollars a year. “The Autonomous Bougainville Government had, by 2016, reached just 6% of the distance to fiscal self-reliance,” Chand found.

Unquestionably there is money to be made on Bougainville: the potential profits to be pulled from Panguna alone have been valued at close to $60bn. But profits for whom?

New president Toroama, once a leader of the militancy that forced the mine to close, says any decision on its future lies with local landowners. “Panguna mine will be a key target but we will not put all our eggs in one basket,” Toroama told Bougainville’s parliament last month in his maiden speech. “We welcome foreign investment, because without outside funding and technologies, we may not be able to exploit our natural resources. But we expect a fair share of return and participation.”

Former rebel military commander Ishmael Toroama, the new president of Bougainville. Photograph: Chris Noble/Reuters

As their elected representative, Matbob is more definitive. Her people must come first.

“Though there is a future for Panguna,” she tells the Guardian from her electorate, “… it will have to be shelved until the needs of my people are well addressed.”

Crowded with outsiders

Bougainville’s acute political uncertainty – poised, potentially, on the threshold of nationhood, with all of its attendant vulnerabilities – has brought ferocious renewed attention on Panguna.

An alphabet soup of foreign mining companies – at least four registered in Perth alone – have sought to carve up the province for future exploitation.

The jostling for position and favour with both the Bougainville and PNG governments has been sharp-elbowed, with accusatory press statements and missives to the stock exchange, even spilling into Australian courts.

Companies have variously accused others of corruption and bribing government officials, of being responsible for environmental vandalism or complicit in military atrocities.

Panguna mine on Bougainville island. Photograph: Reuters Staff/Reuters

And a Chinese delegation reported to have travelled to the province in 2018 was rumoured to have pledged $1bn to fund its transition to independence, accompanied by offers to invest in mining, tourism, and agriculture.

An allied, independent, and resource-rich Bougainville – in the middle of Melanesia and so soon after neighbouring Solomon Islands flipped to recognise Beijing over Taipei – would be of significant strategic value to China.

Even Rio, after years of claiming it could never return to Panguna, has recently indicated it is not entirely out of the picture, saying it was “ready to enter into discussions with communities”.

“We are aware of the deteriorating mining infrastructure at the site and surrounding areas, and acknowledge that there are environmental and human rights considerations.”

For a small island, Bougainville is, suddenly, very crowded.

Matbob understands the enthusiasm of outsiders to return to Bougainville. But for too long, she says, her people’s priorities were subsumed to those of foreign interests, and to profit.

“The Bougainville revolution… was founded on the protection of people, land, environment and culture,” she tells the Guardian.

“Though there is a future for Panguna… there are a lot of legacy issues attached to it. As the new member representing the Ioro people, I say it will have to be shelved until the needs of my people are well addressed.”

SOURCE: The Guardian – https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/17/deal-with-the-disaster-the-girl-from-bougainville-who-grew-up-to-take-on-a-mining-giant

Back to News